My research is driven by a curiosity about some of the deepest questions we can ask:

What is the universe made of, and how did it begin?

Answering these questions requires carefully designed experiments capable of detecting extraordinarily faint signals—often at the limits set by quantum mechanics itself. I work at the intersection of particle physics and cosmology, building and operating precision instruments to search for dark matter and to study the earliest moments of the universe.

While the science spans vastly different scales, from sub-atomic particles to the entire cosmos, the underlying challenge is the same: inventing creative, reliable, and sensitive ways to extract physical truth from extremely small signals.

The large-scale evolution of the universe provides a unique laboratory for testing fundamental physics. By combining astronomical observations with laboratory experiments, we can probe energy scales and physical processes far beyond what is accessible in terrestrial accelerators.

Dark Matter

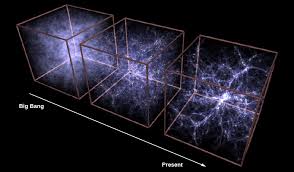

Astronomical observations show that most of the matter in the universe is invisible. Galaxies rotate too quickly to be held together by the gravity of their visible stars alone, clusters of galaxies bend light more strongly than expected, and the large-scale structure of the universe cannot be explained without an additional, unseen component. This missing material— </strong>dark matter </strong>—accounts for roughly 85% of all matter in the universe. Despite overwhelming evidence for its existence, the particle nature of dark matter remains unknown, making it one of the most important open problems in modern physics.

Axions

One particularly compelling dark matter candidate is the axion , a hypothetical particle originally proposed to solve a puzzle in particle physics related to the strong nuclear force. Remarkably, the same theory predicts a particle with properties that make it an excellent dark matter candidate. Axions would be extremely light, electrically neutral, and interact only very weakly with ordinary matter. These properties make them difficult to detect, but also allow them to naturally account for the observed abundance of dark matter in the universe.

HAYSTAC

The HAYSTAC experiment searches for axion dark matter using a technique known as a haloscope . A microwave cavity is placed inside a strong magnetic field, where axions could convert into extremely faint microwave photons. Detecting this signal requires extraordinary sensitivity—far below typical electronic noise levels. HAYSTAC has pioneered quantum-enabled measurement techniques that push beyond traditional limits, achieving world-leading sensitivity across multiple axion mass ranges.

ALPHA

As axion searches move to higher masses, traditional microwave cavities become smaller and less sensitive. The ALPHA experiment addresses this challenge using resonant structures inspired by metamaterials. In ALPHA, the resonant frequency is determined by the effective properties of the structure rather than its physical size. This approach enables searches at higher axion masses while maintaining large detection volumes, opening new parameter space for discovery.

Cosmology

Cosmology seeks to understand the universe as a whole—its origin, composition, evolution, and ultimate fate. Observations on the largest scales allow us to test physical theories under extreme conditions that cannot be reproduced on Earth. Many of the most powerful cosmological probes rely on detecting extremely faint signals, requiring sophisticated instrumentation and careful control of systematic effects.

The Cosmic Microwave Background

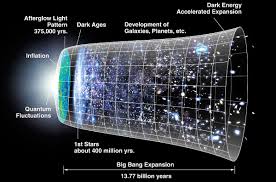

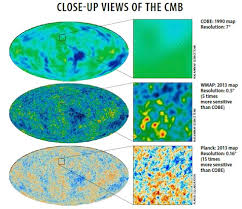

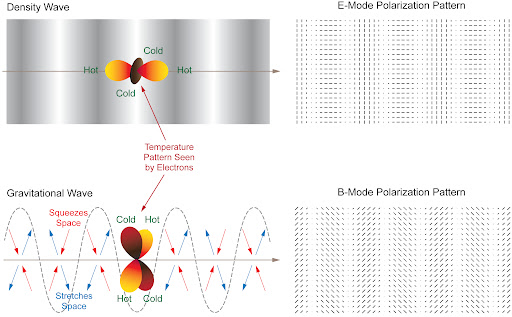

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the oldest light we can observe, emitted when the universe was about 380,000 years old . Today, it appears as a nearly uniform glow of microwave radiation across the sky. Tiny temperature and polarization variations in the CMB provide a detailed snapshot of the early universe, allowing precise measurements of its geometry, composition, and initial conditions.

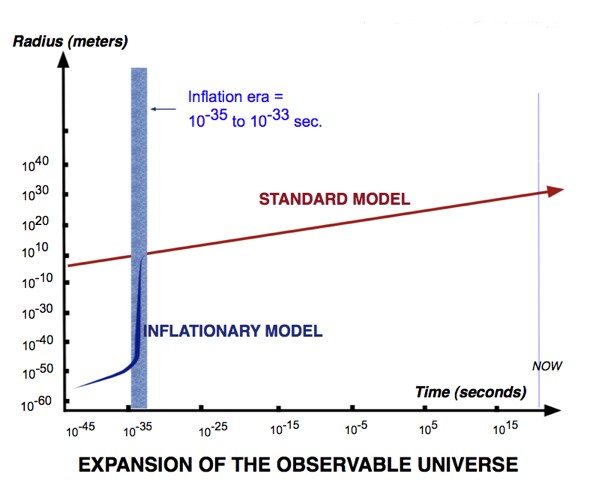

Inflation

Cosmic inflation proposes that the universe underwent a brief period of extremely rapid expansion shortly after the Big Bang. This theory explains why the universe appears uniform on large scales while still containing the seeds of structure formation. Although inflation is strongly supported by observations, its physical mechanism remains unknown. Testing inflation experimentally is therefore a central goal of modern cosmology.

B-modes

A particularly important target in CMB studies is B-mode polarization , a subtle pattern that could be produced by gravitational waves generated during inflation. Detecting primordial B-modes would provide direct evidence for inflation and probe physics at energy scales far beyond those accessible in laboratory experiments. Achieving this requires both exquisite detector sensitivity and precise control of instrumental effects.

Simons Observatory

The Simons Observatory is a next-generation CMB experiment located in the high Atacama Desert of Chile. It combines multiple telescopes with thousands of ultra-sensitive detectors. By improving sensitivity and controlling systematic uncertainties, the Simons Observatory aims to test models of inflation, constrain properties of dark matter and neutrinos, and refine measurements of fundamental cosmological parameters.